It’s been a solid decade since the whole Volkswagen Dieselgate scandal went down, which I think may be sufficient time that we can start saying some things about the whole mess that perhaps we wouldn’t have felt comfortable saying before. Let’s just get the basics all out of the way: it was a terrible thing they did, a miserable nadir of corporate cynicism and greed at the expense of the environment, their own customers, and, really, everyone. It was an indictment of an inflexible and unreasonable management system that forced impossible demands on engineers, and the result was an absolute disaster.

That said, you have to admit that their cheat was pretty clever.

![]()

I don’t think it was ever actually revealed just who had the idea to do this in the first place, but if you think about it, you can see how that diesel train of thought got started. You’re an engineer, working on these diesel engines, and you’re being given performance and efficiency requirements to meet that are simply incompatible with the laws of chemistry, physics, mechanics, and reality in general. And yet, you can’t just tell anyone this, because the corporate culture at Volkswagen at the time was so poisoned and inflexible and unwilling to accept dissent that it was compared to North Korea. Seriously, look at this quote from J.S. Nelson’s paper, Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell Corporate Crime:

The numbers of people involved in the companies is significant as well. In the VW case, there were likely hundreds of people coordinating across at least three companies and five different name brands who made the cheating scheme possible. As the New York Times reports, “[t]he sheer amount of work required to install the software in Volkswagen vehicles suggests that a large number of people were involved.” The defeat-device “software had to be altered for each model and option package.” And these changes had to be made in “11 million tainted diesel engines in more than 30 Volkswagen, Audi, Porsche, Seat and Skoda models, which were available around the world in dozens of variations.” In another indication of how widespread VW’s fraud must have been, despite a company culture described as “North Korea without labor camps,” at least fifty whistleblowers have come forward inside VW after the fraud was publicly revealed who had not previously reported information to authorities.

As you can gather from that, it wasn’t a culture where an engineer could speak up to a manager and explain that the goals for a particular engine were unreasonable. This means that at some point, some engineer or group of engineers found themselves trapped between two immobile barriers: physics and their management. Aside from quitting en masse, what could they do? There was really only one option open to them:

Cheat.

And yes, judge all you want, but you have to respect this act of Gordion Knot cuttery on the part of the nameless engineers who finally came up with the idea. They couldn’t meet the performance and fuel economy goals demanded by their bosses while also meeting the emissions requirements demanded by the governments of the countries they would sell cars into. That much was certain. But, they could meet the performance and fuel economy goals and the emissions requirements on the same car, as long as they didn’t have to do both of these things at the same time! That, I think was the great leap of logic that made this cheat possible.

Once this concept was established, things really started to get clever. They must have realized that performance goals were going to be evaluated, informally, far more frequently than the emissions goals, because regular drivers do not check their emissions. And when emissions were evaluated, it would be formal and rigorous and follow a set pattern. This means that, using sensors and components already on the car, it should be possible to evaluate when a car was just driving, and when it was being tested.

That’s where the clever software came in. Essentially, what this software did was to look for a few key parameters that would, essentially, tell if a car was on a dynamometer or driving on regular roads. These parameters weren’t even all that complex: for example, if the car reads wheel speed over a period of time with no variation at all in steering wheel position over a decent period of time, it can reasonably conclude that the car is on a dyno, strapped down and being tested. If that’s the case, then the software puts the car into a mode where it uses all of the available emissions equipment to get the absolute best emissions cleanliness possible, at the expense of performance and fuel economy.

If the car detects steering wheel position changes consistent with normal driving, it is put into a mode where emissions equipment is bypassed, and the best fuel economy and performance are delivered, at the expense of emissions. The parameters of the test were known, so other factors were checked as well, but checking to see if there was any steering happening is perhaps the easiest to understand.

This is clever as hell. The software that does this essentially gives the car the ability to know its audience. When it’s being tested, it’s an incredibly clean diesel. When it’s being driven, it performs better than most diesels and gets better fuel economy. It teaches the car to play to its crowd.

As far as how it changes its performance and emissions parameters, this Engineering Explained video gives a great rundown:

I’m not even getting into the monkey business here, but trust me, it’s abhorrent. Also, that thumbnail image is unfair; that car is a Brazilian-market Fusca (Beetle) and in many ways those could be some of VW’s most environmentally friendly cars, as many of them ran on sugar cane alcohol, a completely renewable resource.

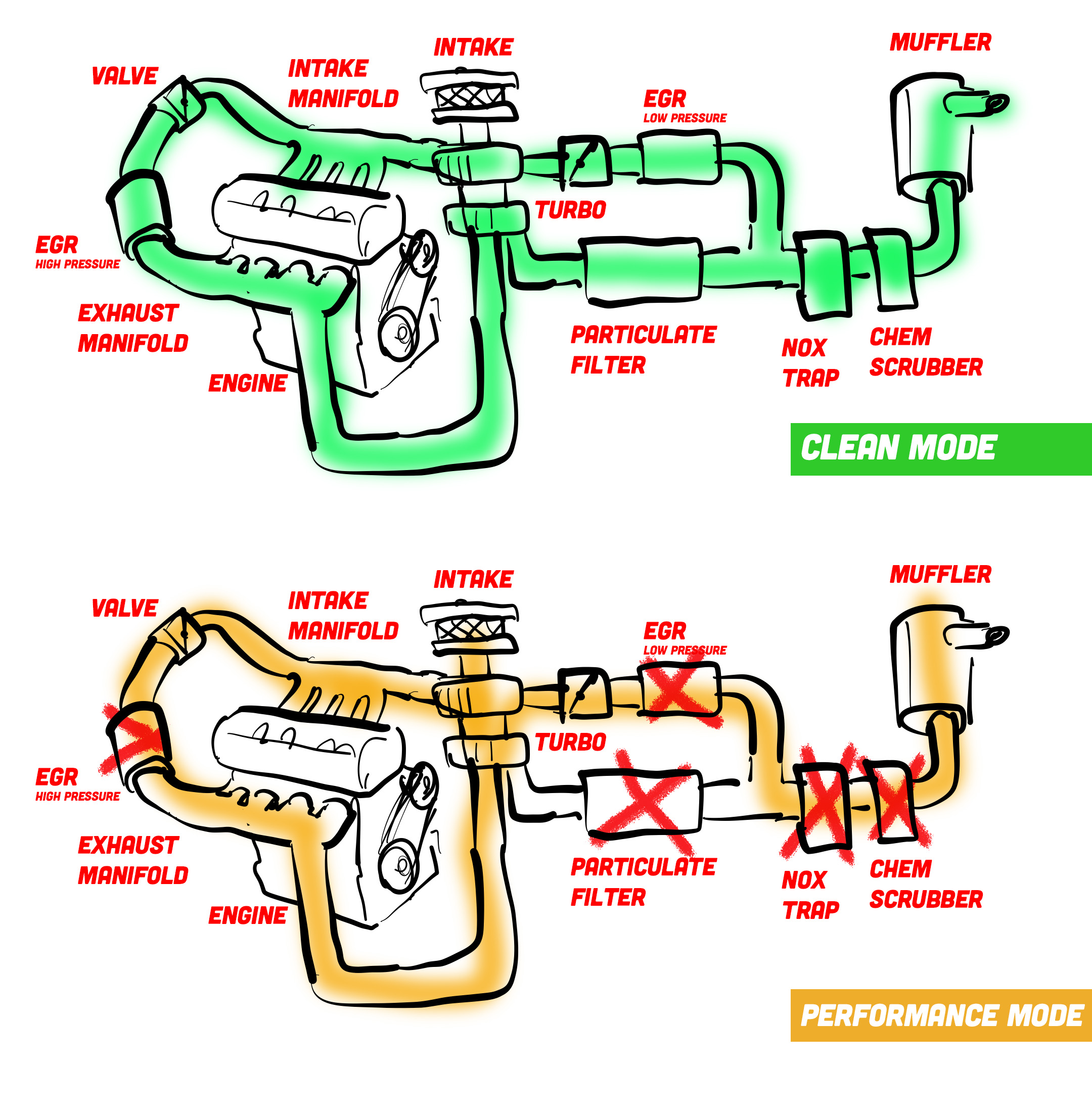

But that’s beside the point; if you can’t watch the video, here’s the basic breakdown of what was happening, as shown on this crude diagram of the engine’s intake and exhaust systems:

So, basically what’s going on is that in clean mode, all of the emissions equipment gets used: fuel/air comes in, the turbo is not spun up all that high (because less exhaust is being routed through it), so the ratio of fuel to air is adjusted to create lower combustion temperatures, which leads to lessened production of nitrogen oxides (NOx), then the exhaust gases get routed back into the combustion chambers via the high pressure exhaust gas recirculatior (EGR) so they go through the combustion process again, then those gases are passed through a series of filters, particulate filters, chemical NOx traps that need to be periodically “cleaned” with fuel, then to another chemical scrubber, and then finally out of the exhaust pipe.

In performance mode, the path is very simplified: air comes in, gets mixed with fuel in the combustion chambers at a much leaner ratio for better fuel economy, then the exhaust bypasses the EGR systems and the various filters – the NOx filter never gets “washed” with fuel, and overall a much less restrictive path for exhaust is made, which gets more power and fuel economy, but also 40 times the emissions!

But that’s just how it works, that’s not really what makes it clever. What’s clever is that it can figure out when it’s being tested, and all the methods used to change the engine’s characteristics are completely invisible, because they are all software changes, using the same hardware. Even though we routinely refer to what VW did as a “defeat device,” the connotation of a device as something physical is misleading, because this was all just zeroes and ones.

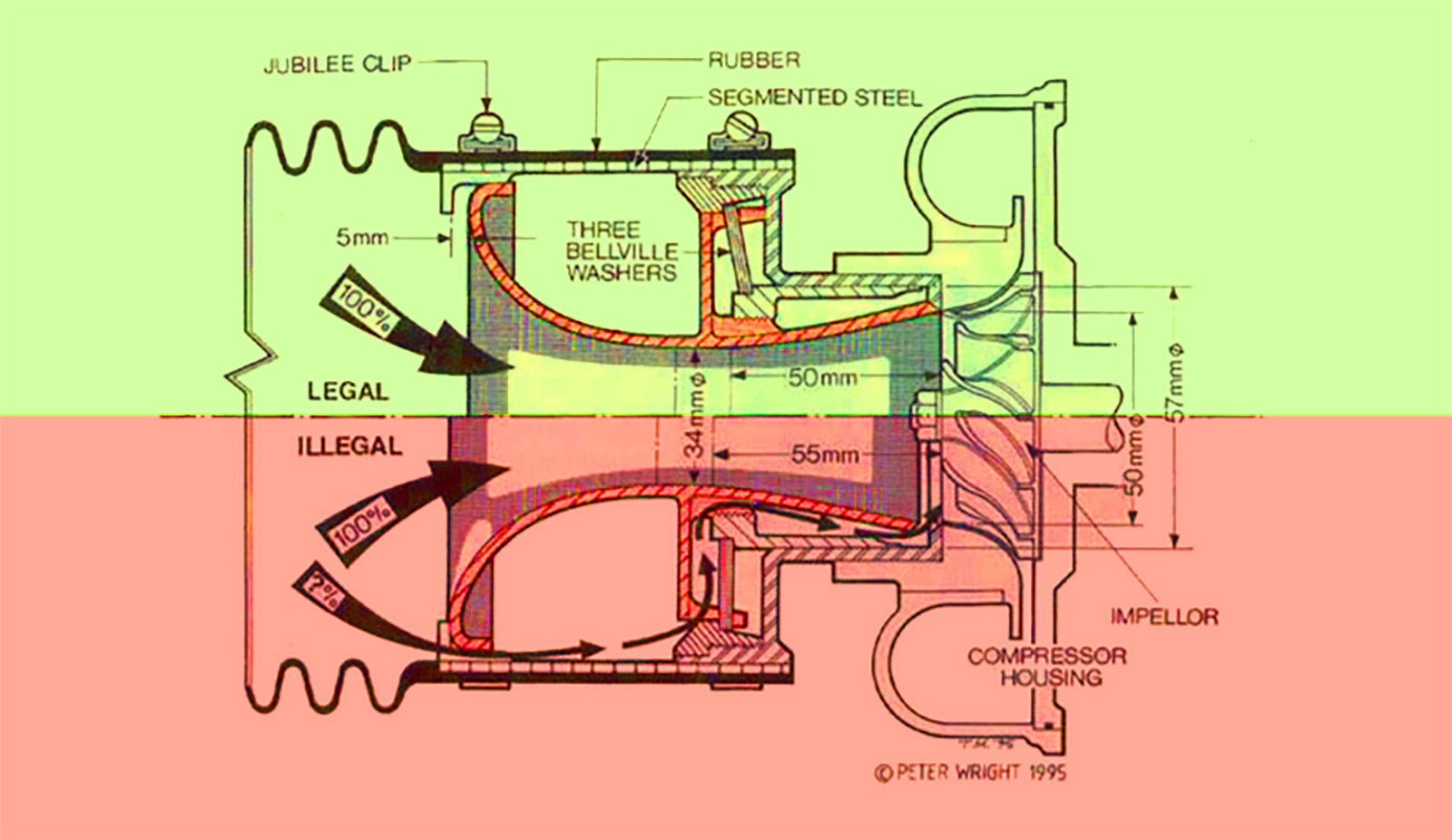

The idea of a machine that understands when it’s being evaluated so it can then hide some aspect of its performance is really pretty uncommon, though I can think of one sort of similar antecedent: Toyota Team Europe’s Turbo Celica cheat of 1995. I wrote about this cheat years ago, and while it’s a mechanical cheat instead of a software-based cheat, the result is the same: when being inspected/tested, the cheat was invisible, effectively non-existent. But when in use, the cheat was very active.

The cheat essentially did one thing: it changed the size of the restrictor plate that was required on cars in that racing series, and changed it to allow for up to 25% more air entering the turbo, which could provide up to 50 extra horsepower. The way it worked involved the use of springy washers that, when pushed by an intake hose and retaining clip, opened the restrictor by an extra 5 mm. But when the hose was removed so the part could be inspected, the springs returned to their baseline position, reducing the intake size to what the regulations demanded.

So, even though this was a purely mechanical solution, this did essentially the same thing as the VW Dieselgate cheat: when being inspected, it appeared to meet all the rules. But when in use, it very much didn’t.

Now, as clever as VW’s cheat was, it was also quite brittle: if the method of testing changed, the cheat would break, because it was only able to understand it was being tested if it matched the expected methods, specifically being on a dyno. So, when the team from West Virginia University tested the cars with portable equipment and drove normally – like, say, using the steering wheel – the cheat broke, because the cars were not able to determine that they were being tested.

This also makes me wonder if the opposite ever happened; did any VW Diesel owner ever take their cars to a dyno to just see what kind of horsepower it made? If so, it’s very likely the car may have decided it was being tested (though perhaps not; it wasn’t just steering wheel position it checked, after all) and then hp numbers would have been a lot lower than expected? But it’s very likely this never happened, as diesel compact car buyers aren’t really the same demographic as people who dyno test their cars to find how much horsepower they make.

I wish there were more details available about how this software actually worked. I’d like to know, for example, what mode these cars defaulted to; did they start in clean mode, just to be safe, or did they start in performance mode, because that’s how they would be used 99.99% of the time? And how long was the evaluation period before a mode was switched? If you were on cruise control on an absurdly straight road, would the car think it’s being tested and switch modes? Could you hit the test parameters by accident? I kind of doubt it, but I’m still curious.

For a while at least, I bet VW engineers thought they pulled it off. I’m also impressed at how quiet it all was kept before the cheat was discovered; hundreds and hundreds of people had to at least be aware that some sort of shenanigans were going on, and yet there was never a major leak about this until those clever researchers discovered what was going on. That’s impressive! Or, terrifying, depending how you think about it. I guess when you’re doing something illegal and you know your job is on the line if it gets out, you’re probably well-motivated to keep it quiet.

We all know that the VW Defeat Device was wrong. Unethical, immoral, unsavory, everything. It’s a painful reminder of capitalism gone off the rails, but I still can’t help but think that what they did was pretty damn clever. And I’m almost certain that this won’t be the last clever cheat we’ll see in this industry. At least, I hope not, perversely.

Source link

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/The-Summer-I-Turned-Pretty-091825-87b73162c1e44126b12cb9216b00b4cd.jpg)