Roughly 50,000 to 60,000 years ago, two groups of Neanderthals were living in caves less than 45 miles apart in what is now northern Israel. One group called Kebara Cave home—tucked into the limestone slopes of the Carmel Ridge. The other settled in the Amud Caves, nestled in the rugged eastern Upper Galilee near a dramatic stone pillar that gave the Amud Stream its name. These ancient humans likely stayed in their caves during the chill of winter, finding shelter and sustenance in the surrounding wilds.

Both groups belonged to a now-extinct lineage of humans that once roamed much of Europe and western Asia through the Ice Age. They hunted with stone tools crafted using strikingly similar methods and went after similar game, mainly gazelles and fallow deer. But here’s where things get interesting: even though they lived so close to each other, these two communities started to diverge in how they lived, and especially, how they handled their prey.

In Kebara Cave, the Neanderthals seemed to hunt bigger animals—like ancient wild cattle (aurochs) and even rhinoceroses—and they brought back more hefty portions of those carcasses than their counterparts in Amud. Both sites show evidence of long-term occupation: layers thick with stone tools and animal bones, fire pits, organized activity spaces, and even human burials.

Curious about how these early humans processed their kills, a team of researchers from Hebrew University of Jerusalem and London’s Natural History Museum zoomed in on something specific: cut marks on bones. That’s right—tiny etchings left behind when Neanderthals sliced meat off their prey with sharp stone tools. Leading the study was PhD student Annal Zalon, working alongside professors Rivka Rabinovich and Erella Hovers, with colleagues Lucille Crate and Silvia Bello. Their findings were just published in Frontiers in Environmental Archaeology.

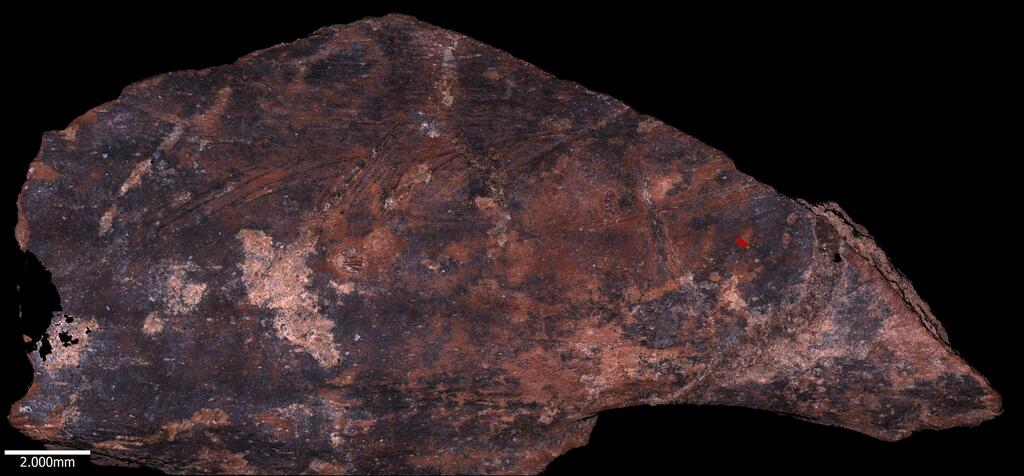

To get a clearer picture of butchery habits, the researchers examined bones with cut marks under both the naked eye and the microscope. They compared bones from similar archaeological layers in both caves, carefully recording the shape, depth, and pattern of each mark. The tools were pretty much the same across the board, so any differences likely came down to technique, not technology.

And differences did emerge. While the overall shape and angle of the cuts were similar, bones from Amud had denser and more irregular marks compared to those from Kebara. In other words, the Amud butchers left more clustered or chaotic cut marks.

So what does that mean? Zalon thinks we might be looking at early cultural fingerprints. “The subtle differences in cut mark patterns between Amud and Kebara may reflect local traditions in processing animal carcasses,” she explains. “Even though they lived in similar environments and dealt with the same survival challenges, the two groups may have developed distinct butchery methods—probably passed down through generations.”

This could point to something big: that Neanderthals didn’t just live on instinct but had social learning, traditions, maybe even “family recipes” for how to carve up a deer. And that means the way they processed food was shaped by more than just efficiency—it might have had to do with how they cooked, shared, or stored meat, or even with how responsibilities were divided among group members.

Of course, the researchers are cautious. “We still have work to do,” Zalon says. “Some of the bone fragments are just too small to tell the whole story. We did our best to correct for that, but there are limits. Experimental studies and broader comparisons will help. And who knows—maybe one day, we’ll be able to piece together a full Neanderthal menu.”