For much of the 20th century, Neanderthals were cast as primitive hunters—robust, spear-wielding hominins whose survival hinged on the relentless pursuit of mammoths and woolly rhinoceroses. Their diets, scholars believed, were almost exclusively meat-based, shaped by the cold, unforgiving climates of Ice Age Europe. But a wave of recent archaeological and genetic discoveries is radically reshaping that view.

At the heart of this shift is new evidence extracted from dental plaque, sediment samples, and coastal excavation sites that suggest Homo neanderthalensis had a far more varied and regionally adapted diet than previously thought. These ancient populations didn’t just chase megafauna—they foraged for mushrooms, cracked open crab shells, and may have even turned to medicinal plants for pain relief. The findings don’t merely reframe their eating habits; they hint at a deeper level of ecological knowledge and behavioral sophistication.

One of the most striking revelations comes from the Iberian Peninsula, where researchers uncovered remains of cooked shellfish, charred seal bones, and pine nuts at Gruta da Figueira Brava, a seaside cave in modern-day Portugal. Dated to between 86,000 and 106,000 years ago, the site paints a picture of Neanderthals who were not only exploiting marine resources but doing so with deliberation and technique. As Professor João Zilhão, the excavation’s lead archaeologist, noted in a 2020 study published in Science, this kind of coastal subsistence strategy had long been associated only with early modern humans.

Parallel discoveries in northern Spain’s El Sidrón cave have unearthed fossilized dental plaque containing traces of poplar bark—a natural source of salicylic acid, the precursor to aspirin—as well as Penicillium, the mold from which penicillin is derived. The individual, believed to have suffered from a painful dental abscess and gastrointestinal parasites, may have been self-medicating. It’s impossible to know whether this was the result of knowledge passed through generations or desperate trial and error, but either scenario points to a sophisticated relationship with the natural environment.

A Regional Cuisine Carved From Necessity

Dietary habits among Neanderthals were far from homogeneous. Stable isotope analyses from bones found in Spy Cave in Belgium show high levels of nitrogen, consistent with a heavily carnivorous diet. The individuals there seemed to rely almost entirely on hunting large herbivores like wild sheep and woolly rhinoceros. Contrast that with their counterparts in the more temperate forests of Spain, where plant-based diets were far more common, consisting of nuts, mushrooms, and other forest edibles.

This variability supports the growing view that Neanderthals were adaptive, not static. As their environments changed—from coastal to mountainous, arid to forested—so did their behavior. “We’re looking at a species that made use of whatever resources were available, often in ingenious ways,” said Dr. Karen Hardy, a paleolithic archaeologist and co-author of the seminal 2017 paper in Nature that analyzed ancient DNA from Neanderthal dental calculus. “They didn’t just survive; they engaged with their ecosystems on multiple levels.”

Even the now-controversial practice of cannibalism, documented at several European sites including Moula-Guercy in France and Krapina in Croatia, has been reinterpreted by some archaeologists. Rather than framing these acts solely as signs of desperation, some scholars suggest they may represent complex cultural or funerary behaviors. While the evidence remains inconclusive, the recurring nature of these findings hints at more than isolated events. As IFLScience recently reported, bone cut marks and burn traces appear frequently enough to suggest patterned behavior.

Blurring the Cognitive Line Between Species

The implications of these discoveries go beyond diet. For decades, anthropologists drew a bright cognitive line between Neanderthals and modern humans, often citing symbolic behavior, long-term planning, and pharmacological use as uniquely Homo sapiens traits. But the more researchers probe Neanderthal living sites and remains, the harder it becomes to defend that boundary.

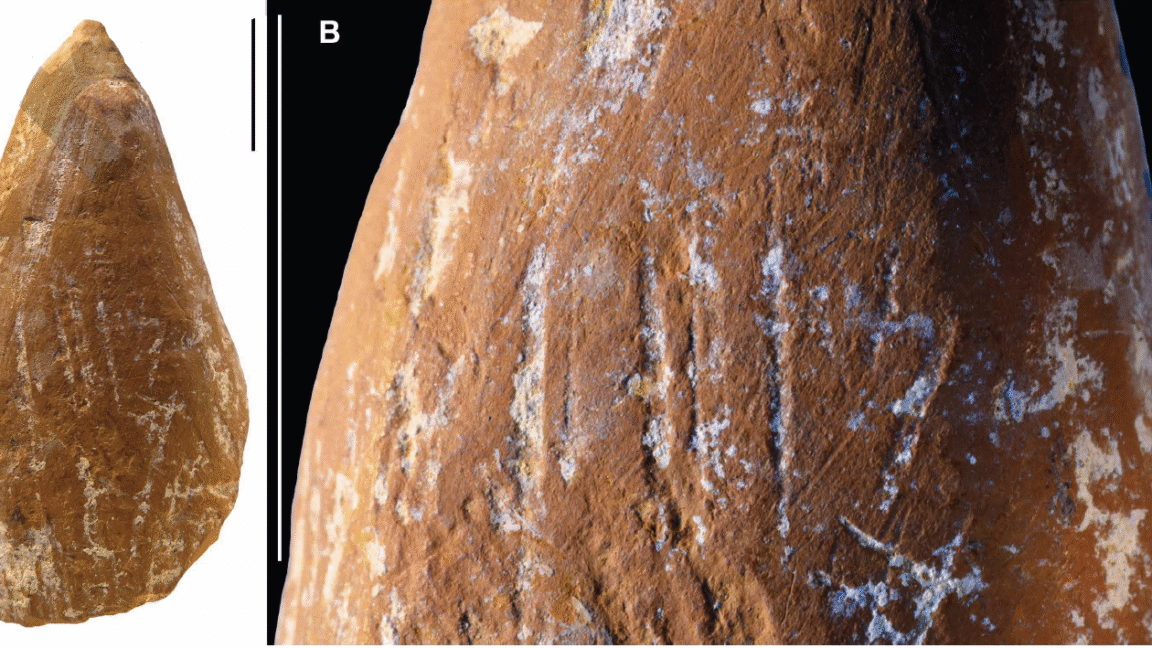

Neanderthals at Figueira Brava, for instance, appear to have engaged in seasonal foraging, storing unopened pine cones to be cracked open later by fire. This kind of delayed-return behavior is a hallmark of complex cognition. And while Neanderthal cave art remains contentious, findings like those at La Pasiega and Ardales—which suggest symbolic use of ochre and marine shells—are gaining acceptance in the scientific mainstream.

In terms of health and microbiology, recent studies have even revealed that Neanderthals hosted oral microbes remarkably similar to those found in modern humans, hinting at shared evolutionary pressures and lifestyles. A comprehensive study in Nature Ecology & Evolution (2021) showed that gut microbiota patterns have remained surprisingly stable over tens of thousands of years, bridging modern and ancient populations.

Reassessing the Paleo Narrative

These revelations are pushing scientists to reconsider not just who Neanderthals were, but what it means to be human. The notion of a “real” Paleolithic diet—often romanticized in modern nutrition trends—is increasingly shown to be a myth. As Hardy and colleagues point out, Paleolithic diets were hyperlocal, dependent on geography, climate, and seasonality. There was no single template.

More importantly, the growing body of evidence from coastal Portugal to the forests of Spain underscores that Neanderthals were not a footnote in human evolution. They were a branch of the hominin family tree that independently developed a rich, context-driven way of life—one that now feels much more familiar than alien.

Source link